A Brief Q-and-A: What’s the House Doing, How Will the Senate Deal With It and What Will Happen to Trump?

The House of Representatives is working in clear, constitutional control of the second impeachment of Donald Trump.

In impeachment, the House handles a constitutional, pre-trial process within its massive, “sole” power, while the Senate—once it receives the charges from the House—handles the impeachment trial in its “sole” power. The word “sole” appears only twice in the Constitution—to define the broad power of the House and Senate in impeachment. The process has a centuries-old, constitutionally clear purpose: to protect our country from harm.

If the Senate convicts (by a two-thirds vote) on any one charge (“article”), the president automatically is removed from office. The then-removed, former president, however, would not be disqualified from future office-holding. The penalty of disqualification is not automatic on impeachment conviction. To disqualify an impeached-and convicted now-former high officer, the Senate needs to undertake a second vote.

Without the disqualification vote—which requires only a majority in the Senate—the impeached, convicted, disgraced, removed, former high officer may run for office again. The Constitution sets no time limits for the disqualification work.

Here are some questions and answers about the impeachment process:

Question: What is Impeachment?

Answer: Impeachment is a congressional trial process; it’s neither a civil nor a criminal trial.

The House files and prepares the case in its constitutional “sole” power, developing charges known as “articles.” The House decides when to vote and, if any article passes by a majority, presents the adopted charges to the Senate, which handles the trial of the case in its “sole” power, serving as judge and jury, ruling on legal issues during the trial. In the Senate trial, House members act as prosecutors (“managers”). In the case of presidential impeachment, the Senate trial is presided over by the chief justice of the Supreme Court. Although chief justices sit in impeachment trials of presidents, they have no powers; they are figureheads.

Q: Impeachment is not a criminal process; it’s a congressional process to protect the country.

A: Although impeachment requires no evidence of criminality and no criminal penalties attach to impeachment, the House pleads and attempts to prove ongoing harm in a variety of ways. The House includes evidence of various bad motives and intent, such as corruption, incompetence, gross misconduct or incapacity, even though they are not required; all such evidence helps demonstrate persistent, ongoing threats to our country, our people and system of government.

The Framers focused on harms from an out-of-control president; they described impeachment as superior to the alternative of “tumults and insurrections,” praising it as the proper way to deal peacefully with the “misconduct of public men” as they focused on injuries done by high civil officers of the new country to “society itself.”

Q: Who regulates impeachment?

A: The House alone begins and regulates its impeachment conduct. The Senate alone has the final say in the conduct of the trial of impeachment. Impeachments aren’t appealable. The Supreme Court, led by the late impeachment scholar Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, made clear that this important constitutional grant of “sole power” means that the Senate need not even conduct a judicial-style trial; not “a single word in the history of the Constitutional Convention … even alludes to the possibility of judicial review in the context of impeachment powers” (Nixon v. United States, 506 U.S. 224, 228-38 [1993]).

Q: If the Senate votes to “convict” what happens?

A: Separate from conviction, the Senate may vote on whether to impose the constitutional penalty of disqualification from future federal office-holding.

The Senate trial “conviction” is not a criminal conviction. The constitution is clear that the possibilities in “Judgment in Cases of Impeachment:” are limited to “…removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of Honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.”

Q: Removal is automatic upon conviction (requiring two-thirds vote), but the disqualification from future office-holding (requiring only majority vote) is not automatic.

A: In the Senate, by historical precedent and scholarly consensus, the officer charged automatically is removed from his office upon a two-thirds vote of the senators present to convict. This longtime understanding of automatic removal is consistent with Rehnquist’s constitutional writings, particularly his concern for chaos due to lack of finality during appeals or retrials (Nixon v. U.S., 506 U.S. at 236).

While a two-thirds vote on any article results in automatic removal, there’s no automatic disqualification. The Constitution does not require a two-thirds vote on the disqualification issue, so a majority suffices. In the 1913 impeachment trial of federal Judge Robert W. Archbald, the corrupt, coercive judge was disqualified for future office holding on a 39 to 35 Senate vote.

The Senate decides when and how to disqualify. In the 1936 impeachment case of Judge Halsted L. Ritter, the Senate convicted Ritter by a two-thirds vote on only the last of six articles. No removal vote was necessary as Ritter was considered automatically removed.

After that, the Senate held a disqualification vote that Ritter survived. He was not disqualified from future office-holding.

So it’s clear: After the first guilty finding resulting in the automatic removal of the high officer, the Senate retains jurisdiction over the impeachment and continues to fulfill its responsibility to continue to work on the case, with multiple, pending issues involving more votes on additional articles. In the old days, some Senates chose to hold another, separate vote for removal and properly holding cases to vote on disqualification issues. Building a record provides evidence for subsequent votes, proving key elements such as risks of harm if an officer were not disqualified. All such additional votes fill the historic records.

Q: Who runs the timeline for impeachment?

A: The congressional sole powers of impeachment allow the House and Senate to make their own decisions, each in their own time, serving impeachment’s purpose to protect the country from harm, particularly in preventing the convicted, harmful former officer from holding federal office in the future.

The House decides when to vote and when to present articles to the Senate. The House may choose to delay the presentation. The Constitution places “sole” power with the Senate on how and when to try the case.

Q: So, may Congress, with these “sole” constitutional powers, hold on to this Trump impeachment No. 2 so they eventually can take votes to convict and, separately, disqualify Trump from future federal office holding?

In history, the House has delayed presenting articles, and the Senate repeatedly has continued their work and votes on impeachment matters after officers have been removed automatically with a conviction on one article. The historical fact is that the Senate often deals with high former officers, still in impeachment mode.

The Framers considered impeachment a key power to prevent the destruction of the United States. James Madison, a key debater at the Constitutional Convention responsible for the Impeachment Clause, worried that a president’s “Loss of capacity or corruption was more within the compass of probable events and either of them might be fatal to the Republic.”

The houses of Congress will not be wasting their time in carefully tending to their Constitutional Impeachment duties.

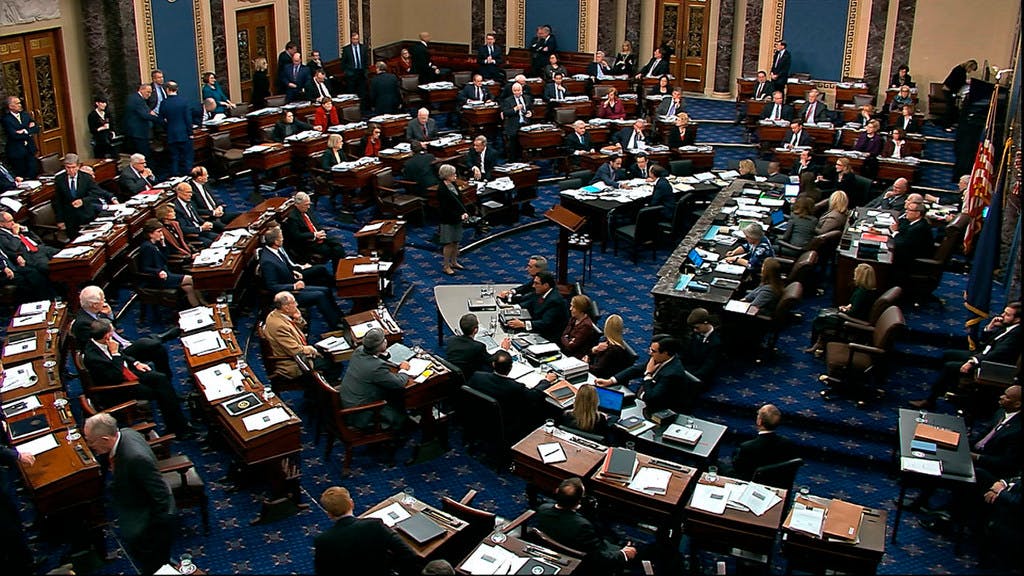

Featured image: The Senate during the first impeachment trial of Donald Trump, Jan. 23, 2020. (Senate TV)

Barbara Radnofsky is an attorney and mediator teaching and practicing in Houston. Listed for more than 25 years in Best Lawyers in America in multiple categories, she is the author of Melville House’s A Citizen’s Guide to Impeachment, in which quotations and citations referenced in this article may be found.